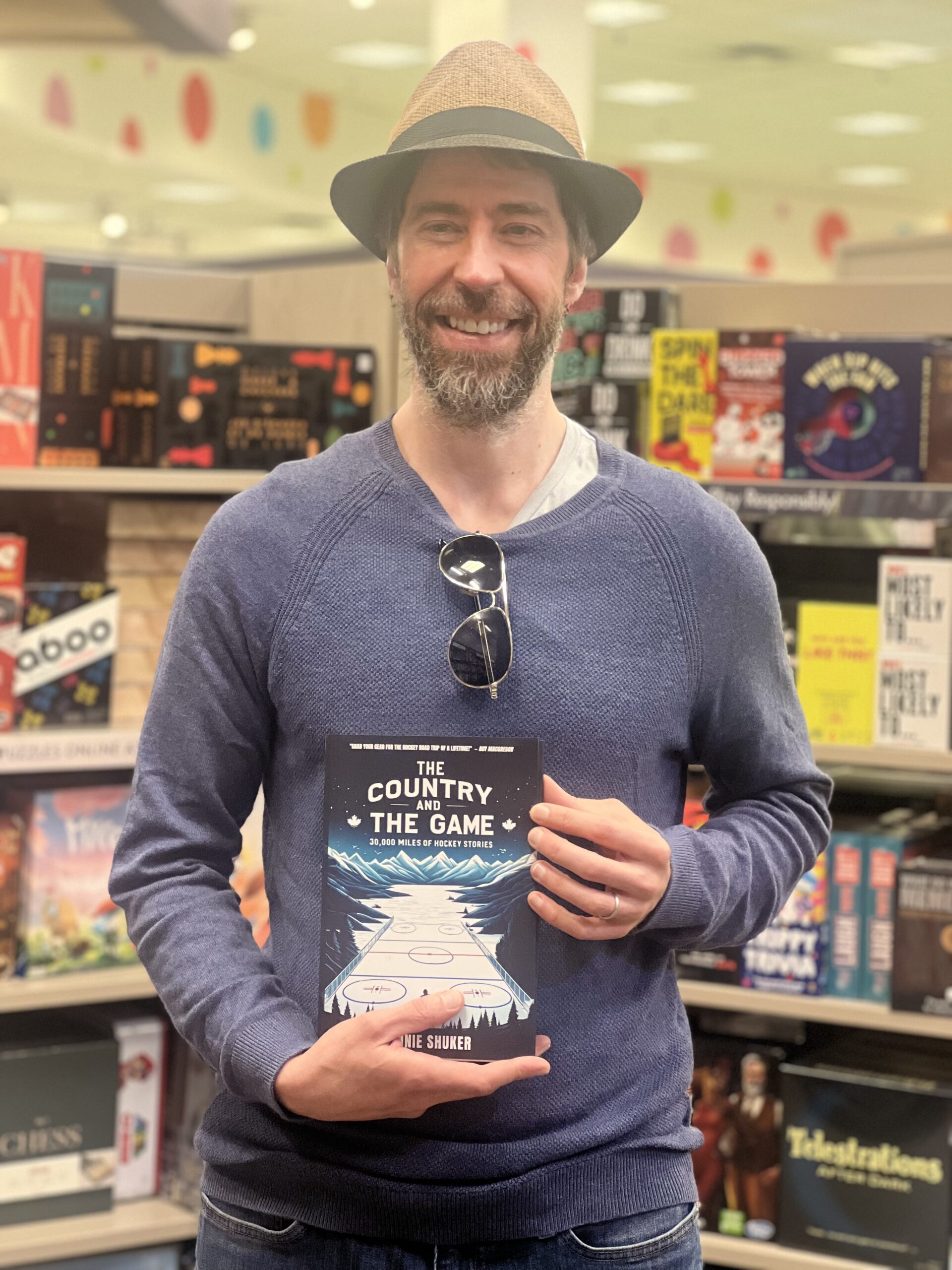

The following is an excerpt from the Book ‘The Country and the Game: 30,000 Miles of Hockey Stories’ by Ronnie Shuker

The next day, I begin the long drive home from Vancouver, some 4,800 kilometers (3,000 miles) east to Toronto. Five hours in, I stop in Kamloops.

I arrive at the Hamlets at Westsyde, sign in, do a rapid test for COVID-19, and walk upstairs to my father’s spartan room; just a bed, a chair, and not much else. The fewer the number of things, the less confused he gets. The staff are good to him, like he is their own father or grandfather. I told them I wanted to try to take him to a Kamloops Blazers game tonight, and when I walk in he’s sitting quietly in a chair, showered and shaven, wearing his Blazers cap and jacket. I like to think he was waiting for me.

At least his pants are on right. When he was still living with my mother, in their downtown condo, he would sometimes come out of their room with his pants on backward. At first, I muffled my laughter, then I began letting it out and my father would laugh, too. We would laugh together, me knowing what was coming and him knowing nothing at all. When it got so hard that he needed full-time care, I would do and say all the things any son blessed with a good father wished he’d done and said years earlier. I would hug him fiercely, kiss him on the cheek, and tell him I love him.

It started out harmless enough, back when my parents were still living in Cedar Valley, a hamlet just north of Toronto. “Mild cognitive impairment,” the doctors said. Then came the ghosts my father started seeing at home while my mother, an air ambulance nurse, was away picking up ill and injured tourists in some far-flung part of the world. The ghost tales were easy enough to shrug off in a century-old farmhouse with untold stories in its walls. But then came the day when my father called my younger sister from a parking lot, telling her he couldn’t find the car. Then came another, a few years later, after we’d sold the family farm and moved my parents out to Kamloops, when someone from the YMCA, just a few hundred feet from my parents’ condo, called my mother to tell her my dad couldn’t find his way home while walking the dog.

Every unwritten rule of life goes out the window when dealing with dementia. The only option is to figure it out as it goes along and treasure the rare moments of lucidity. You hold onto those for your life, as long as you can. Like the time my father looked me square in the eyes as we sat at the kitchen table and said, out of the blue, with a lucidity and clarity I hadn’t seen from him in years, and haven’t since, “You know, son, I’ve always loved you.” For those who suffer from the disease, it is almost always something non-linguistic that brings them back, however fleeting it may be. For many it is music, for others it is some other activity or hobby, like painting, baking, gardening, or arts and crafts. For my father, until even it lost its magic, it was hockey.

For whatever reason, from whatever region in his deteriorating brain that somehow remained intact, hockey became a brief reprieve from the dementia, whether it was watching the Maple Leafs or Canucks on TV or catching the Blazers live in Kamloops. When the game was on, the hallucinations disappeared. Gone were the conversations with ghosts, the phone calls from the news anchors on CNN, the boats floating down the middle of street, the robbers trying to steal his stuff. He stopped trying to stick a knife into the toaster “to check if it’s alive” and didn’t stare at the chair cushions “waiting for them to move.” Normally he would’ve struggled with even basic commands, like “sit down” or “put your shoes on.” Yet when hockey was on, he seemed to understand concepts like offside, icing, powerplay, and penalty kill. For a few hours, it was nice not having to pluck the Raisin Bran out of the refrigerator or the butter from the dishwasher. It was just father, son, and the game.

For years, my father had been a loyal subscriber of The Hockey News. As his dementia got worse, he began poring over every issue, like he was under some kind of deadline, as a former journalist, marking up the margins and taking notes—pages and pages and pages of notes.

“I know, I know,” he would say to me. “Who’s that crazy goof who never gets anything done? That’s me, right?”

Winter road trips were a staple of my childhood. Like most hockey dads, my father’s days off were spent schlepping his son to long-distance road games or tournaments. When I wasn’t practicing at some god-awful early morning hour on weekdays before he went to work or playing games on weeknights and weekends, he was taking me door-to-door throughout our neighborhood so that I could raise enough money selling cookies, baked goods, or whatever else kids guilt their neighbors into buying just so they can play on the ice at Maple Leaf Gardens for the Timmy Tyke Tournament. My father knew that his son would never be one of the 0.00025 percent of kids who make the NHL. He was never a deluded hockey dad. He sat in the stands among the crazy hockey parents and never pretended it would ever amount to anything other than his son having fun playing the game, learning whatever life lessons hockey has to teach. He never yelled at me after a game, never told me what I did wrong, and never cursed any coaches, although he did give it to a referee once during a road game when I was crosschecked headfirst into the goalpost and the hometown officials said play on. I’d never seen my father, as meek and mild a man as I’ve ever known, get angry before. He screamed at the officials so loud and so long, he got kicked out of the arena.

Our family never could afford tickets to see the Leafs play, not even in the 1980s when the team was comically bad. Instead, my father took me to American Hockey League games when the Leafs’ farm team was briefly housed in Newmarket, a short drive from the farm. The closest thing to any NHL game we ever went to was an exhibition affair between the Leafs and Moscow Dynamo at Maple Leaf Gardens, and later an intrasquad game that the Leafs played in Newmarket during training camp. I remember that game for Wendel Clark, who wallpapered teammate Brad Smith into the boards and sent him out on a stretcher. It was preseason, Wendel.

After picking up my father, I drive us downtown to the Sandman Centre and walk him to the ticket gate. As we cross the road, a young man takes my dad’s hand and helps me get him across. You would think being around all these people would make my father anxious or agitated, but crowds seem to calm him. He doesn’t stray, unlike the time he left the condo in the middle of the night in the dead of winter and the police brought him home.

When I find our aisle, the usher lets us sit in a pair of seats at the end of an empty row, where I won’t have to keep getting my father up and down for others to walk past. To keep him from wandering, I’ve brought four blueberry muffins. By the end of the first period, they are gone. A couple behind me, Alex and Stephanie Bell, can tell I need help. Over the next two periods, as my father and I watch the Blazers run away with the game, Alex and Stephanie keep bringing my father food, including three hot dogs, a bag of popcorn, and a supersize Coke. For every drill sergeant coach, overzealous hockey parent, or deluded beer-leaguer, there are a thousand good people in the game. I can’t thank Alex and Stephanie enough.

Kamloops is set to host the Memorial Cup after I return home from the road trip, so the Blazers are stacked with talent. They aren’t the Blazers of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the team had such future Hall of Famers as Mark Recchi, Scott Niedermayer, and Jarome Iginla, but they’ve assembled one of the best teams in the Western Hockey League. They win easily tonight, giving me the victory I was hoping for.

After the game, the crowd starts filing out of the building. Sensing I need help, a security guard stops people from coming up the stairs in our aisle so that I can get my father out of his seat. No one protests. Everything went right that night.

I walk my father back to the car and fasten his seatbelt around him, much the way he did for me as a kid before I could manage on my own. I pull out of the parking lot and wait patiently for a break in the dispersing crowd. I look over at my dad. He looks calm and quiet, warm and puffy in his Blazers jacket, with his Blazers toque tucked tight around his ears. I don’t know what he is thinking, but he seems peaceful and happy. I smile as I pull onto Mark Recchi Way and drive him home.